Equine Oral Health Resources

We’re dedicated to helping you better understand your horse’s dental health and the importance of routine care. Here, you’ll find valuable information on common dental conditions, procedures, and tips for maintaining your horse’s oral health. Our goal is to empower you with the knowledge you need to ensure your horse stays comfortable and performs at their best.

Dental Care for Senior Horses

As horses age, their dental needs evolve significantly, requiring specialized care to keep them comfortable and healthy in their golden years. The goal for senior horses is to maintain their quality of life by preserving as many functional teeth as possible while addressing the unique challenges that come with aging. Regular veterinary dental care is essential for helping senior horses thrive despite these changes.

Horse teeth don’t grow indefinitely—they erupt from a finite reserve within the skull. Over time, the chewing process wears down their teeth, eventually leading to smoother surfaces. Unfortunately, this wear isn’t always even, leaving some teeth too tall or overly worn. As a result, older horses may struggle to chew coarse feeds like hay, which can impact their ability to maintain weight and proper nutrition.

To help senior horses with worn teeth, diets should include easier-to-chew alternatives like senior feed or soaked hay pellets. These options mimic "pre-chewed" food, breaking down quickly with saliva to accommodate reduced dental function. Proper nutrition is vital, as most horses need to consume about 2% of their body weight daily to maintain their health.

Periodontal Disease: Periodontal disease is a painful condition common in aging horses, stemming from uneven tooth wear. This creates gaps where food collects, causing inflammation and infection. Early stages of the disease may be managed with regular dental care, but advanced cases can lead to severe infections and tooth loss.

EOTRH (Equine Odontoclastic Tooth Resorption and Hypercementosis): This progressive disease affects the incisors and canines, causing pain and difficulty in eating, grasping hay, or accepting a bit. The condition can significantly disrupt a horse’s daily life, and the only treatment is removing the affected teeth.

Equine Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID): Also known as Cushing’s disease, PPID impacts the pituitary gland and weakens the immune system. Horses with PPID are more prone to infections, including periodontal disease and sinus infections. Untreated dental issues in these horses can become life-threatening, highlighting the importance of regular veterinary exams.

Thanks to advancements in veterinary medicine and nutrition, horses are living into their 30s and beyond, despite their teeth being biologically designed to last about 15 years. Regular dental care, combined with a tailored diet, play a crucial role in ensuring older horses remain healthy and happy well into their senior years.

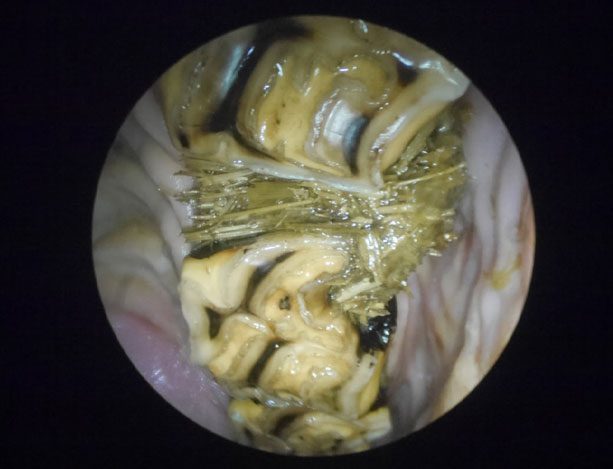

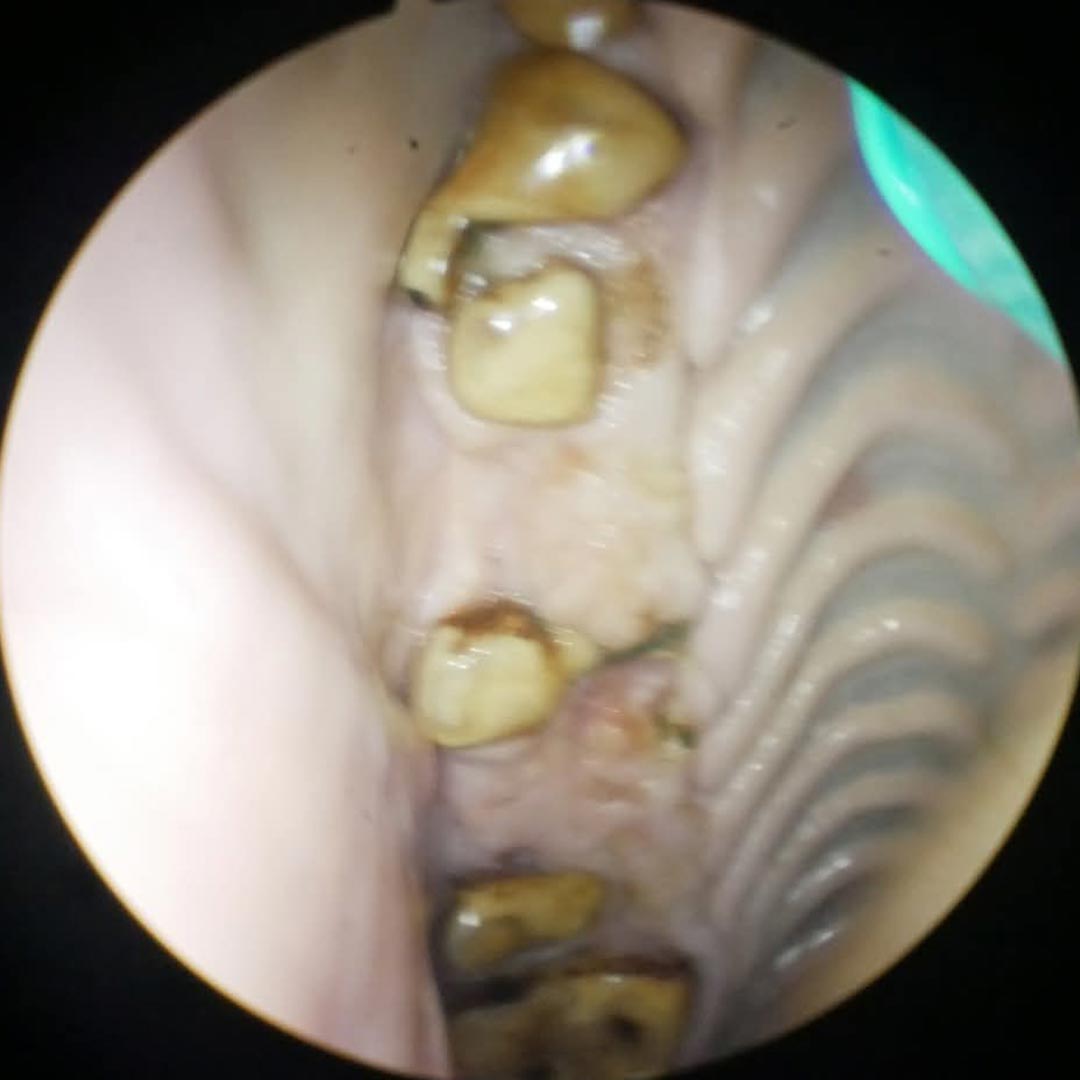

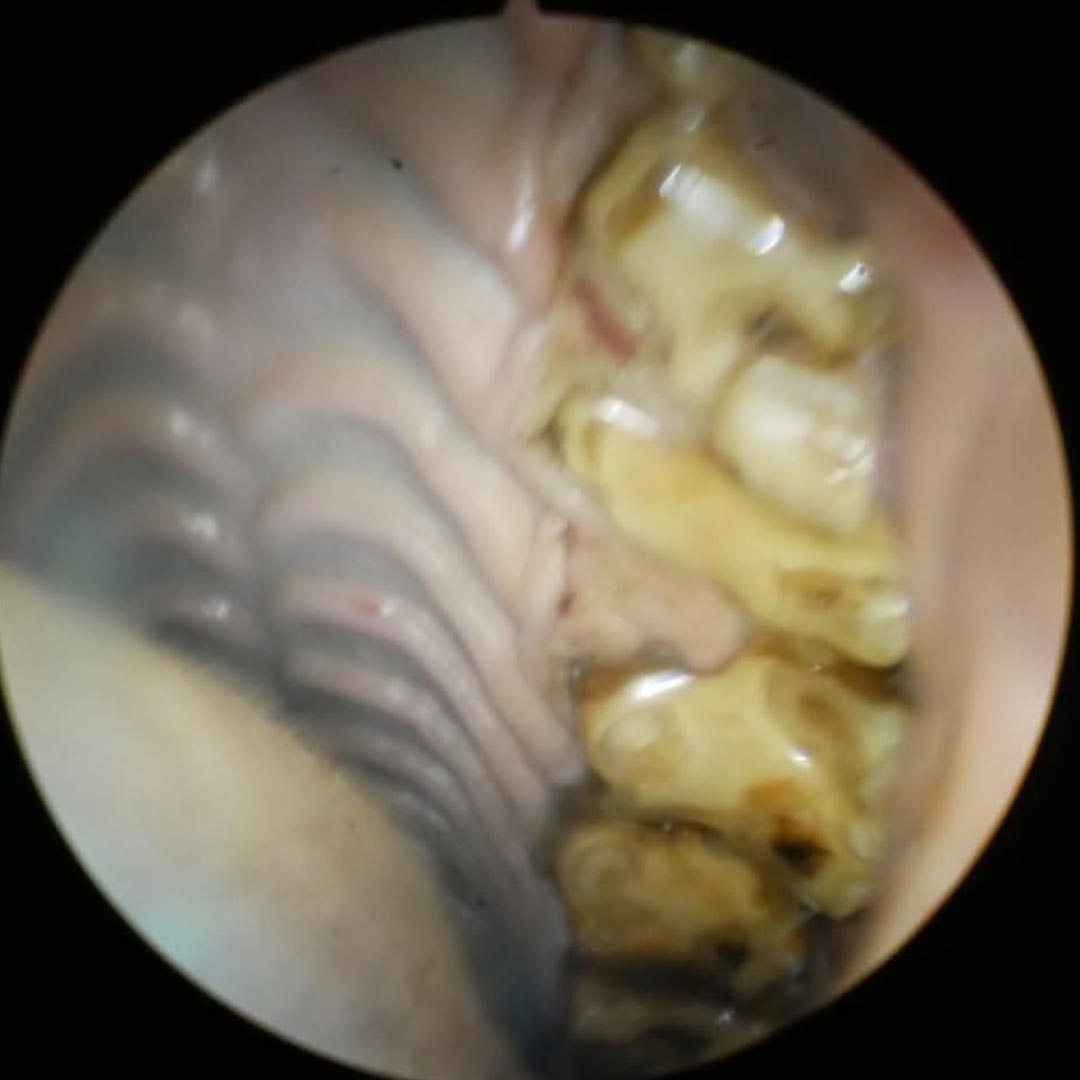

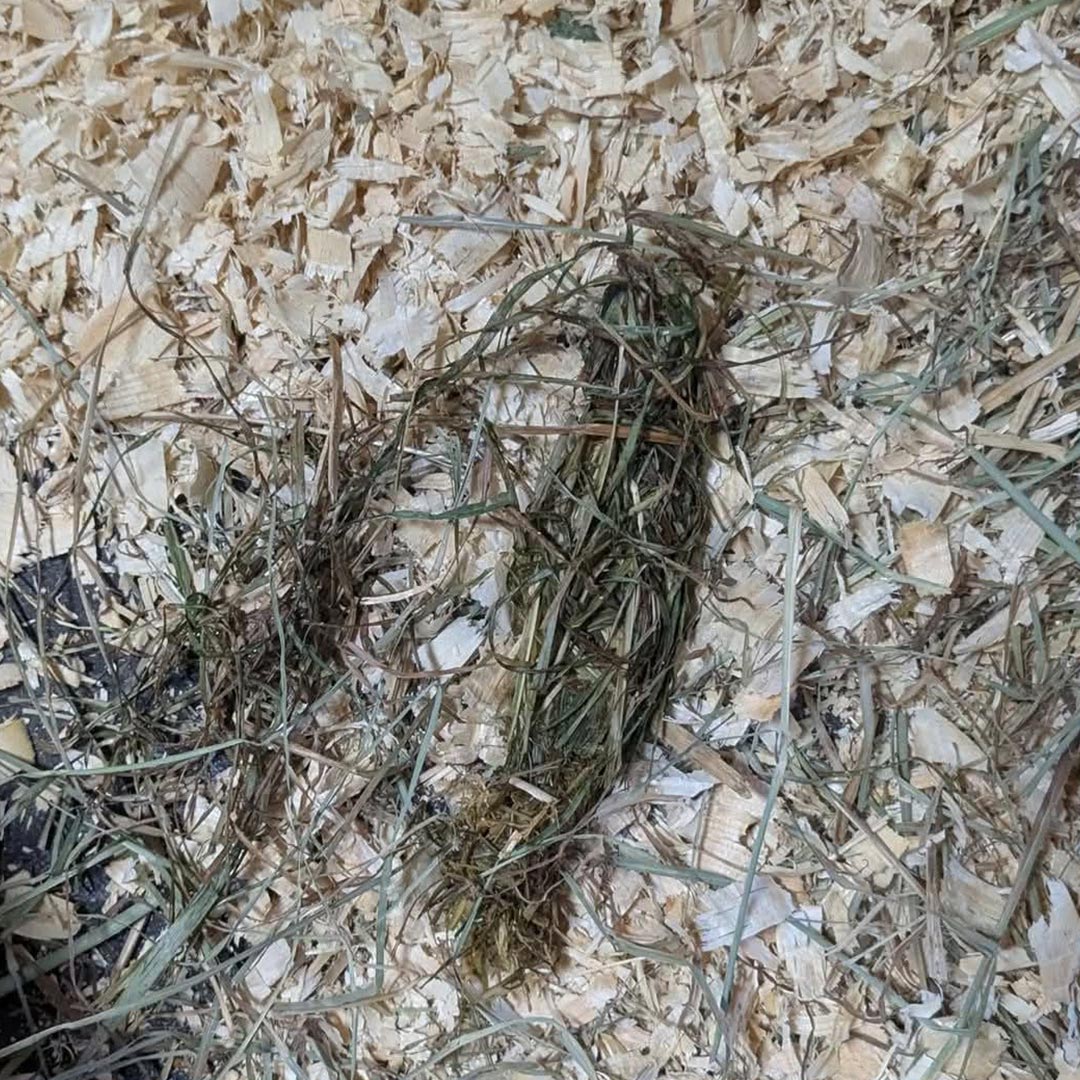

These photos and video show a senior horse over 30 years old. If you turn up the volume, you’ll hear a squeaking sound when he chews. This happens because his cheek teeth are reaching the end of their lifespan.

With age, his teeth have worn down significantly due to geriatric attrition. As seen in the photos, his teeth are now completely smooth, with many reduced to just retained roots. Normally, a horse’s teeth have a rough surface to grind food efficiently—similar to a rasp. However, in this case, they have become smooth like glass, leading to the distinctive squeaking sound when he eats.

One of the photos also shows a “quid”—a wadded-up ball of hay that he is unable to chew properly and ends up spitting out.

Although he no longer requires routine floating, regular dental exams remain essential. Worn-out teeth can become loose and uncomfortable, affecting his comfort and ability to eat. Thanks to a well-managed feeding program, this horse remains in excellent body condition, proving that with proper care, a horse can outlive its teeth and continue to thrive.

Equine Odontoclastic Tooth Resorption and Hypercementosis (EOTRH)

EOTRH is a painful and progressive dental condition most commonly seen in older horses, affecting their incisors and canine teeth, and occasionally the molars. This disease occurs when the body begins resorbing (dissolving) affected teeth, leading to attempts at repair through the deposition of extra dental tissue (cementum). Unfortunately, this compensatory process creates weak, irregular structures, leaving the teeth vulnerable to fractures, loosening, or even falling out. These changes often allow bacteria to invade, causing inflammation of the gums (gingivitis), surrounding structures (periodontitis), and the tooth's live inner tissue (pulpitis).

For more information about EOTRH, you can listen to the Disease Du Jour podcast episode Dr. McAndrews was a part of here.

The exact cause of EOTRH remains unknown. While some theories suggest abnormal wear as a contributing factor, this has not been proven. A study investigating hormonal imbalances in affected horses also found no definitive links but did note a higher prevalence in geldings.

EOTRH is a painful condition, though its gradual progression often makes it difficult to detect. Many horses adapt to the discomfort, masking the severity of their pain. Common signs include:

- Difficulty chewing or decreased appetite, especially for grazing

- Weight loss or irritability when ridden

- Sensitivity to pressure on the teeth

- Fractured, missing, or loose teeth

- Swollen, red, bulbous, or receding gums

- Incisor rubbing

Some horses exhibit no outward signs, underscoring the importance of regular veterinary checkups.

Since much of the disease process occurs beneath the gumline, radiographs are essential for diagnosis. Radiographic abnormalities may include:

- Resorptive lesions, shown by areas where the tooth is dissolving

- Bulbous cementum, or irregular deposits of excess cementum around the tooth

Currently, there is no way to halt or reverse the progression of EOTRH. The only proven treatment is the extraction of affected teeth. The extent of extraction depends on the disease stage—mild cases may involve a single tooth, while advanced cases often require the removal of all incisors.

Removing all affected teeth at once is typically the best course of action for the following reasons:

- It eliminates the source of pain completely.

- Horses undergo only one surgical procedure, reducing stress and recovery time.

- It lowers the overall cost compared to multiple surgeries.

Horses recover remarkably well after extractions, often resuming normal eating habits immediately. They learn to use their lips for grazing and can return to riding once their gums have healed. Most owners report significant improvements in their horse’s comfort and demeanor post-surgery, realizing the extent of their pain only in hindsight.

This case involves an 18-year-old Selle Francais gelding, a competitive upper-level dressage horse, referred for evaluation of EOTRH. The owner noticed behavioral changes when the horse was ridden with a bit, prompting further investigation.

Diagnosis

Radiographs revealed mild to moderate EOTRH across all incisors, with the corner incisors showing the most severe changes. The horse’s central incisors were less affected, but still showed signs of disease.

Treatment Plan

For EOTRH, the only effective treatment is the removal of the affected teeth, which often involves extracting all incisors. However, the horse's role as a competitive dressage horse added a layer of complexity. Dressage penalties can occur if a horse consistently hangs its tongue out of its mouth, a behavior that can sometimes follow full incisor extraction.

We discussed the option of leaving the less affected central incisors to potentially prevent this, while explaining that these teeth might still cause pain and could require removal later. The owner ultimately prioritized their horse's immediate comfort and chose to proceed with the extraction of all incisors to eliminate the source of pain and avoid a second procedure in the future.

Procedure

The horse was sedated, and regional nerve blocks were used to numb the area. All incisors were extracted, with post-extraction radiographs confirming the successful removal of the affected teeth.

The horse returned home the same day and resumed a normal diet and turnout immediately. The only restriction was no riding with a bit for three weeks.

Outcome

Five weeks post-procedure, the horse is thriving. Not only is he comfortably wearing a bit again, but he also naturally keeps his tongue tucked inside his mouth—a fantastic outcome for a competitive dressage horse.

We are thrilled with this horse’s recovery and are excited to see this remarkable team back in the show ring. This case is a testament to the importance of timely dental care and the resilience of our equine athletes.

Secondary Dental Sinusitis

Have you ever noticed thick, malodorous discharge coming from one nostril of a horse? One of the most common causes of this is sinusitis, or a sinus infection.

Horses have several sinus cavities, including the ventral conchal and maxillary sinuses, which are located near the upper molars. The roots of these molars are only separated from the sinuses by a thin layer of bone, making them vulnerable to infection. When a tooth becomes infected, the infection can spread into the sinus cavity—this is known as secondary sinusitis. Secondary sinusitis is typically caused by an underlying dental issue, such as a tooth infection, periodontal disease, cyst, or mass.

In contrast, primary sinusitis is caused directly by a bacterial or fungal infection, without any underlying dental problem.

A horse with sinus disease may develop one-sided nasal discharge of thick white or yellow pus or mucus. Blood may also be present. You will also likely notice a distinctive unpleasant odor coming from one nostril.

If left untreated, a dental infection can progress into a serious sinus condition. Over time, the sinuses can fill with fluid, pus, and even food, causing significant discomfort. While antibiotics may temporarily clear up the infection, they often fail to completely eradicate it. This is because bacteria can hide within the infected tooth, and once antibiotics are discontinued, the sinus infection will return.

An oral examination, endoscopy and radiographs will help to confirm a secondary dental sinusitis. To fully resolve secondary sinusitis, the infected tooth must be extracted—antibiotics alone are not enough.

Regular dental exams by a veterinarian can often catch infected teeth or periodontal disease before they cause sinusitis.

In the CT image below, the sinuses appear black, indicating they are filled with air. However, on the left side of the image, you can see a tooth with an apical infection and a surrounding gray area, indicating that the sinus is filled with material. When an infection progresses this far, sinus surgery may be needed to remove the inspissated (thickened) material in addition to extracting the infected tooth and providing antimicrobial treatment.

In the CT image below, the sinuses appear black, indicating they are filled with air. However, on the left side of the image, you can see a tooth with an apical infection and a surrounding gray area, indicating that the sinus is filled with material. When an infection progresses this far, sinus surgery may be needed to remove the inspissated (thickened) material in addition to extracting the infected tooth and providing antimicrobial treatment.

This case involved a mare presenting with a six-week history of left-sided malodorous nasal discharge. Despite antibiotic treatment, the symptoms persisted. Upon oral examination, the mare was found to have an enlarged lymph node on the left side of her head, along with nasal discharge. Additionally, she had a complicated crown-root fracture and caries (decay) of the 209 tooth.

Diagnosis and Imaging

Radiographs revealed a tooth root infection in the 209 tooth, which had led to secondary sinusitis.

Challenges with Cheek Teeth Extractions

Cheek teeth extractions can be particularly challenging due to dental interlock—the teeth are so tightly packed together that it becomes difficult to maneuver them within the tooth socket (alveolus). This issue is often worse in young horses with larger teeth or in cases where the teeth are fractured, causing adjacent teeth to shift into the space of the fractured tooth.

To overcome these challenges, a partial coronectomy technique was used. This procedure involves removing a sliver of the mesial (front) or distal (back) portion of the tooth to create more space for extraction, allowing the tooth to be moved more easily within the socket.

The Partial Coronectomy Procedure

Given that the crown of the 209 tooth was already fragile due to the previous fracture, the decision was made to perform a partial coronectomy. The procedure involved carefully removing a sliver from the distal aspect of the tooth to provide more room to manipulate the tooth during extraction.

By doing this, the tooth was successfully extracted without causing further fracture to the remaining crown.

Post-Operative Care

Post-operative radiographs confirmed that the entire tooth was successfully extracted. The alveolus (tooth socket) was packed with dental impression material to aid in healing and was removed approximately two weeks later. The mare continued antibiotic treatment for another two weeks to ensure the sinus infection resolved.

With proper treatment, the sinus infection was cleared, and the socket healed effectively.

This case involved a 28-year-old Warmblood gelding with a more than one-year history of left-sided malodorous nasal discharge. Despite several rounds of antibiotic treatment and a partial extraction of tooth 211 by a lay person, his nasal discharge persisted. Upon oral examination, the horse showed faint malodor from the left nostril and had an enlarged lymph node on the left side of his head. There was no active nasal discharge at the time of the exam. His 209 tooth was worn down to the gum line due to his age, and his 210 tooth was fractured with fragments of the 211 still present.

Diagnosis and Imaging

Radiographs revealed:

- Periodontal disease and tooth infection in the 209 and 210 teeth

- Retained fragments of the 211 tooth

- Evidence of a sinus infection, likely secondary to the tooth infections

Challenges and Procedure: Tooth Extraction via Sectioning

The patient was sedated, and the left side of his head was numbed using a local nerve block. The 209 tooth was so worn down from age that there wasn't enough crown left to grasp with forceps. Normally, a tooth with no crown to hold onto would require a sinus surgery, which is highly invasive with a risk of complications. However, in this case, we opted to section the 209 tooth into two halves using a specialized burr. This technique allowed us to extract each half individually, avoiding the need for more invasive surgery.

Additionally, the 210 tooth was also extracted, as it was fractured. The retained roots of the 211 were left in place.

Addressing the Sinus Infection

Since horses with secondary sinus infections due to dental disease often have two separate infections (the tooth infection and the sinus infection), the first step was to extract the infected teeth. While antibiotics may resolve the tooth infection, sinus infections, especially chronic ones, require additional treatment.

In this case, sinus surgery was necessary. The sinus infection had persisted for so long that the mucus in the sinuses had become thick, similar to cream cheese, preventing it from draining properly through the small sinus passageways. Antibiotics alone could not penetrate or clear this thickened material.

To address this, a local surgeon performed a sinoscopy, a minimally invasive procedure involving a small, quarter-sized hole made in the sinus. A flexible endoscope (a small camera) was inserted to inspect the sinuses. Specialized instruments were used to flush and remove the infected material from the sinuses.

Outcome

After the tooth extractions and the sinus surgery, the nasal discharge resolved, and the horse recovered. The horse’s sinus infection was successfully treated, and his condition improved significantly, marking a positive outcome for this case.

PPID and Dental Disease in Senior Horses

Equine Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID), also known as Cushing’s Disease, is a common condition affecting senior horses, particularly those aged 15 and older. This disease impacts the pituitary gland, causing it to produce excess hormones that can lead to a variety of symptoms.

- Long, curly coat that does not shed properly (a hallmark sign)

- Muscle loss and abnormal fat deposits

- Excessive sweating and laminitis

- Repeated infections, including skin infections, hoof abscesses, periodontal disease, and sinus infections

While our practice specializes in equine dentistry, and not in the diagnosis or treatment of PPID, we are acutely aware of the effect PPID has on dental care, particularly in senior horses.

Horses with PPID are more susceptible to infections due to the altered hormone levels, which impair the immune system and hinder healing. This makes them particularly vulnerable to periodontal disease and sinus infections, both of which can lead to severe health complications if not managed promptly.

When treating senior horses with advanced dental disease, we highly recommend testing for PPID and initiating treatment before proceeding with aggressive dental interventions, such as tooth extractions or sinus surgery. If PPID is left untreated, dental issues can escalate and become life-threatening.

If you suspect that your senior horse may have PPID, consult your veterinarian to have blood tests performed. Testing for PPID is not recommended during the fall months, as the incidence of false positives is higher during this time.

What Are Wolf Teeth?

"Wolf teeth" are the first set of premolars in a horse’s mouth, though they are often misunderstood. Despite their name, they serve no real purpose in the horse’s ability to chew or process food. Instead, these small teeth are remnants from the horse's evolutionary ancestors and have little to no functional role today.

- Size and Shape: Wolf teeth can vary greatly in size, shape, and location from horse to horse. Some horses may have one, two, or even up to four wolf teeth, while others may have none.

- Location: Wolf teeth are located just in front of the first premolars, right before the long block of premolars and molars that are responsible for chewing.

- Age of Appearance: These teeth typically erupt between 6 to 18 months of age, and many horse owners opt to have them removed before the horse starts training or wearing a bit.

While wolf teeth don’t affect chewing, their position in the mouth makes them prone to interfering with the bit, which can cause discomfort or behavioral issues under saddle. Not all wolf teeth cause problems, and some older horses with wolf teeth may not experience any issues under the bit. Each horse is different and we elect to remove them based on their location, their size, their likelihood to cause problems, or if they're already causing problems.

It’s important not to confuse wolf teeth with canine teeth, which are much larger and typically only found in male horses (although mares can sometimes have them too). Canines, or "fighting" teeth, sit in the interdental space (between the incisors and pre-molars) and do not interfere with the bit. Canines should not be removed unless they are diseased or fractured, as their removal can cause significant complications.

- Procedure: Extracting wolf teeth is relatively simple but depends on the horse’s age and the condition of the tooth. The horse is sedated, and the area around the tooth is numbed with a local anesthetic. The tooth is then elevated and extracted using forceps.

- Challenges in Older Horses: In older horses, wolf teeth may have more attachment to surrounding tissues and may be more difficult to remove, with the root sometimes fracturing during extraction.

- Blind Wolf Teeth: Occasionally, horses can have "blind" wolf teeth that never fully erupt through the gum line. These can cause issues, especially under the bit, and often require radiographs to properly locate and remove them.

We recommend sedated oral exams for young horses before they start training, especially to check for wolf teeth. Removing wolf teeth early—ideally by age 3—can prevent potential issues and ensure a smooth start to training and bridle work. Proper dental care is key to a horse’s comfort and performance.

Oral Masses

Oral exams are about more than just the teeth. Many different kinds of oral masses can develop in horses. While some of these masses are luckily benign and just bothersome, some can be painful and deadly. Some common oral masses are papillomas, melanomas, and squamous cell carcinoma. Only during a sedated exam with a speculum, light, and a mirror can these masses be visualized and biopsied for a proper diagnosis.